|

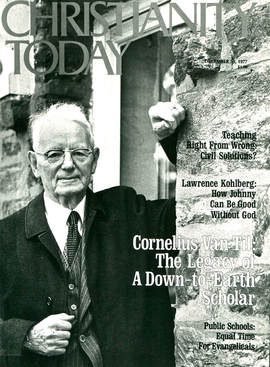

I wrote this article first as a paper for a Historical Theology class when I was at Wheaton College back in 2014. As I look it over a full 10 years later, I would say that it's not bad - but it's also not a great paper. All that say, take what's good and ignore what's not so good. The gentlemen at Reformed Forum do a fine job in their discussions of Van Til. Compare what I say to what they have done a great job in fleshing out.  hen Cornelius Van Til published the 1955 version of his The Defense of the Faith, he was responding to a backlash of objections to the apologetic methodology he had previously articulated.[1] Until Van Til had introduced his new and unique method, apologetics had been understood and practiced in a drastically different light. In the history of the church, apologetics had usually drawn most of its attention from that of philosophers. The common characteristics that set apart apologetics as an intellectual branch of theology usually bore the following marks: (1) it argued for a generic or general theism; (2) it was dominantly by informed and grounded in philosophy rather than biblical theology;[2] (3) it was considered a separate field distinct from evangelism.[3] These broad, sweeping generalizations of how apologetics had been traditionally conducted are what made Van Til’s thinking so unique, because his thought was contrary to the historical model as well as the status quo. In contrast, Van Til’s apologetic methodology bears the following characteristics: (1) it argues for a specific Christian-theism; (2) it is grounded directly in scripture over philosophy;[4](3) it is informed by a distinctly Reformed theology; and, (4) it is practiced with and alongside evangelism. In the words of Greg Bahnsen, Van Til’s contributions to apologetics “brought about the reformation of Christian apologetics.”[5] Historical Context To begin to make sense of Van Til’s thought, it is important to understand that it takes place within a specific context. Like all contexts, the meaning contained therein sheds light onto the catalyst of Van Til’s thought, and what makes his contribution to the church and its theology profound and full of new, meaningful insights. The context of Van Til’s life came, in many respects, at a turning point in the life of the church. Many Enlightenment ideas, specifically those of Immanuel Kant, were influential in shaping the general thought that surrounded Van Til’s life. A handful of these ideas included (1) the rejection of authoritative revelation from God, (2) the autonomy of the human mind, and (3) the intelligibility of human experience.[6] A Darwinian view of human history, which became more dominant during the life of Van Til, stressed an upward progression of humanity and was likewise skeptical of revelation from any god. If there was a god, it did not necessarily have to be Jesus Christ, and it did not require a special or some sort of specific revelation to know him. In other words, humanity already possessed all the tools available to them in evidences and reason to rationalize and understand God (if they concluded there was such a deity) independent of revelation.[7] Some of this thinking corresponded to the emergence of German Higher Criticism which, being full-blown in the 1920’s, placed greater doubts on the reliability of the Bible—specifically, its divine inspiration. Although there is more detail that could be provided, it is these general threads of modernist thought that dominated and comprised the context into which Van Til was born. Biography Van Til was born in 1895 in the Netherlands. By way of picturing this time period, this was also the same year Babe Ruth and J. Edgar Hoover were born, the year the first professional football game in America was held, and the year Louis Pasture died. Van Til, who was nicknamed Kees, was born into a Dutch Reformed family of farmers and celebrated his 10th birthday while immigrating to the United States.[8] His family moved to Indiana, where Van Til grew up. He was educated at the local preparatory school and later went on to college and graduate school. Upon his enrollment at Calvin Seminary, Van Til already knew English, Dutch, Latin, Hebrew and Greek.[9] After spending just one year at Calvin Seminary, he transferred to Princeton Theological Seminary, which had been historically known at this time for its academic prowess and influence. Van Til excelled in his studies, eventually moving on to gain a ThM in systematic theology and a PhD in philosophy.[10] His intent upon graduation had originally been to pastor a small church in Michigan in order to be closer to home, but his plans began to change the year he began teaching. Following only one year of teaching at Princeton, he was offered the chair of Apologetics, which he subsequently accepted but shortly resigned. During this time, Princeton reorganized along modernist[11] lines to which Van Til, as well as several other more conservative faculty—including J. Gresham Machen[12]—deemed as breaking with the “Old Princeton Tradition”, and moreover, allowing liberalism to take control of the seminary.[13] Van Til returned to Michigan and pastored for only one year before accepting the invitation from Machen to be the chair of apologetics at the newly founded Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. Van Til taught for more than 45 years at Westminster, published 30 books and syllabi[14], and over 200 articles. His work undoubtedly led to him being offered the Presidency of Calvin College, which he declined in order to remain in his post at Westminster. Despite the complexity and level of Van Til’s thought, he was known to step out of his academic role from time to time and engage in activities such as street preaching in New York. As many biographers and followers of Van Til have noted, he possessed a pastoral heart and often engaged in conversational evangelism to those surrounding him—including long walks with Roman Catholic Nuns that lived behind his home in Philadelphia.[15] Van Til’s thought, in the words of John Frame, was often not clear, sometimes not cogent, but incredibly profound.[16] His fresh insight into the field of apologetics, uniquely, added virtually nothing new to theology; instead, it stood more firmly within the reformed theological tradition to bring about a consistency in apologetics. This was the backdrop for Van Til’s book, The Defense of the Faith. The Defense of the Faith Van Til, as it seems, did not primarily desire to add anything new to theology. Rather, he desired for apologetics to be consistent with what had already been articulated by many others. While he was at Princeton, Van Til noticed that Reformed theology did not inform the predominant apologetic that was taught. Much of Van Til’s work in apologetics can be seen as a reaction against this insufficient theological foundation that persisted at Princeton and beyond. Prior to Van Til, apologetics had lacked a clearly articulated biblical and theological foundation. This is perhaps why Van Til’s critiques did not seem to know what to make of his work, because in their eyes, it was entirely new. Because of this, his critics often contradicted each other in their criticism of his apologetics. Van Til’s work integrated several key themes: 1) Presuppositionalism 2) Reformed theology 3) Creator-creature distinction 4) Noetic effects of sin 5) Covenantal Relationship & the myth of neutrality 6) Impossibility of the contrary (of the opposite) and pressing the Antithesis 7) Appeal to ultimate authority Presuppositionalism Van Til’s methodology, often referred to as “presuppositionalism,” is not the clearest term.[17] What is puzzling and often frustrating is that Van Til never actually defines “presuppositionalism,” and seems to have only used it by way of accommodating academic discussions with his critiques.[18] John Frame defines a presupposition as a “basic heart commitment.”[19] Though, as Frame points out, there are a few instances where Van Til uses the term in different ways. In these instances, the range varies from “necessary precondition,” “ultimate authority,” to “starting point” or “reference point.”[20] Part of the reason that presuppositionalism is a lacking term is that everyone holds their own presuppositions. Thus, the term doesn’t denote anything specific or articulate its meaning very effectively. When Van Til used the term, he was referring to a specific, ultimate presupposition: his belief in God. Nonetheless, the term remains ambiguous as many today place themselves in a “presuppositional” camp—though there are a number of “sub groups” within presuppositionalism. The most common misunderstanding of this label is that the presuppositionalist is only concerned with presuppositions. Hence, Scot Oliphant calls it “a bad term—there are many presuppositional types out there.”[21] In actuality, the term “presuppositions” is meant to denote one’s ultimate authority. When addressing the subject of epistemology, the presuppositionalist aims to expose the ultimate presupposition—the deepest held belief—of his counterpart. He drives deeper and deeper into his counterpart’s worldview until he finds his deepest belief—or in other words, his highest standard of truth. This is partly why the term is a bit vague, as it is not descriptive of what Van Til held as his own. Van Til’s starting point—ultimate authority and deepest presupposition—was the divinely inspired scripture.[22] Notably, in Van Til’s Introduction to Systematic Theology written 20 years later, Van Til still begins with the Doctrine of God as revealed in scripture.[23] The fact that Van Til begins his thought with Scripture and with biblical theology (as discussed later on) strikes most as “customary.” This, however, is precisely the point and main thrust of Van Til’s thought. If apologetic methodology does not begin with scripture and theology, then it is not being grounded on what is professed as belief. In other words, it would be inconsistent. This is the argument of Van Til—apologetics is not to be pursued separately from theology; rather, it must be informed by it so as to be consistent with God’s revelation. Highest Degree: Not the Least Common Denominator As Van Til lays out in this text, Christians “are not to define the essence of Christianity in terms of its lowest but rather in terms of its highest forms.”[24] In saying this, Van Til was responding to what he labeled as the “traditional method” of defending the faith, which sought out the fewest and most basic commonalties between both the non-believer and the believer, as well as between different Christian traditions. Often this is the case for modern day apologetics to seek the “mere Christianity” approach of defending the faith to avoid the differences that lie, for example, between the highly nuanced and articulated theology of both the Reformed and Arminian traditions- which quite obviously, stand in contrast to each other on several points. Van Til saw this as adequate and less than biblical, for as he articulates in his own approach, one’s theology will inform one’s apologetic.[25] The value of Van Til’s epistemology is that it “[…] observes to the non-Christian that if the world were not the way Scripture says it is, if the natural man’s knowledge were not actually rooted in the creation and knowledge of God, then there could be no knowledge whatsoever.”[26] This leads directly into the Creator-creature distinction. Creator-Creature Distinction Van Til makes frequent reference to the creator creature distinction. In Van Til’s thought, it is not merely a subtle distinction, but rather an impassable chasm.[27] Contained in this distinction is the way in which humanity learns of God. In Van Til’s understanding, humanity can only know of God if he condescends to humanity. Although humanity receives a general, natural or universal revelation of God’s invisible attributes, this revelation can only serve to damn human beings. Without special revelation, humanity cannot know who God is.[28] Along with this comes the more sophisticated talk of epistemology. Van Til’s aim, therefore, was not to convince the non-believer that God exists; for according to Romans 1, all people know that God exists, yet they “suppress the truth.” Rather, he aimed to show that there is no epistemological basis for rejecting God or suppressing the truth. Furthermore, because the world is the way God made it to be, it is expected that all in a state of sin will reject knowledge God, or vehemently Him. The noetic effects of sin are what cause the unregenerate person to suppress the truth of God. The distinction between the creature and the Creator does not allow humans to be autonomous in their reasoning, and therefore fully relies upon God to make sense of reality.[29] Put in another way, they must borrow capital from a Christian worldview that recognizes the distinctions of both worldviews, but also the creator and the creature. The Lordship of Christ creates the dependence for all humanity to function upon the preconditions which the Creator has made. Because Christ is authoritative, “it must be the believer’s starting point.”[30] Noetic Effects of Sin The “noetic effects of sin” is a technical way to describe the fallen condition of man’s reason. This view is distinctively Reformed and stands in contrast to Roman Catholic theology, or Natural Theology.[31] Van Til uses the analogy of a bent saw. The saw is bent at its origin, and no matter how good the operator of the saw is, the boards are always flawed, because the saw is flawed from its starting point.[32] The noetic effects of sin are an extension of the Creator-creature distinction, which illustrates humanity’s inability to reason without God regenerating and redeeming a sinful man’s mind. This is not to say that humanity lacks the ability to reason, but they lack the ability to justify or regenerate their reason outside of the will of God. The ability to reason at all is the result of common grace and common mercy that God bestows on both the regenerate and unregenerate.[33] This relates in part to the commonalty that the believer and non-believer have in common: they are both image-bearers of God. One needs additional grace to have a restored mind.[34] This distinction is further enhanced by Van Til’s understanding of humanity in covenant relationships with God. Covenantal Relationship & the Myth of Neutrality There are two ways to describe the importance of covenant in Van Til’s apologetic. Prior to Van Til, most apologetic methods had failed to appreciate—or simply ignored—the fallen nature of humanity, and the radical antithesis that exists between believer and unbeliever. Under covenant, humanity is either in Adam or in Christ. There is no middle ground or third option to appeal to. What this means is that the Christian must do apologetics on the basis of his covenant relationship with Christ in order to show the non-believer that, if they do not stand in Christ, there is no ground to stand on. The only other ground is in Adam and outside of Christ—a place of condemnation. “Deep down in his mind every man knows that he is the creature of God and responsible to God. Every man, at bottom, knows that he is a covenant breaker.”[35] This covenantal relationship leaves no middle ground, no neutral territory on which to conduct a apologetic arguments. Apologetics can only be done on the basis of a covenantal perspective in which the Christian meets the non-believer (who is inescapably made in the image of God) at a point of contact—though he suppresses the truth of God in unrighteousness.[36] This debunking of the idea of intellectual “neutrality” created the preconditions for Van Til’s methodological engagement with the non-believer, and it illustrates one of the key components of Van Til’s apologetic method. Having recognized that humanity is helplessly fallen (as Scripture says it is), Van Til refused to argue for God on the basis of probabilities, or to build upward from the common facts shared by the believer and unbeliever. Rushdoony describes the “natural man’s” insistence of this point: “[T]he religious hangers-on of autonomous man and his philosophy are insistent that their emperor be allowed all but his overcoat, that natural man be allowed valid knowledge of everything except God and matters pertaining to revelation.”[37] Van Til describes entering into the apologetic scenario not to prove a reasonable God to “natural man,” but as Van Til puts it, to show “the impossibility of the opposite.”[38] The Impossibility of the Contrary This leads to a key distinctive of Van Til’s approach. Many involved in the apologetic discourse will ask, “how do you prove the existence of God?” As Van Til described it, through the impossibility of the opposite. Van Til used this to describe what he saw in light of all the theological discussion already mentioned. Without God, humanity reduces itself to absurdity. Humanity must both assume upon the world in which God created the basis to reason, and while in sin, suppress the truth of God. The job of the apologist, according to Van Til’s assessment in this text, is to expose that inconsistency and show the unbeliever that he is borrowing capital from the Christian worldview—for “every method, the supposedly neutral one no less than any other, presupposes either the truth or the falsity of Christian theism.”[39] Locating the inconsistency can be difficult, because inasmuch as humanity is diverse in worldviews, religions etc, the systems that men contrive to suppress God’s truth are often quite sophisticated. This is the point in which the believer “steps into the other person’s shoes” and answers the fool according to his folly. For the sake of argument, the apologist takes on that person’s worldview in order to illustrate to the non-believer that they do not and cannot consistently believe what they are espousing; it is not consistent, workable, or justifiable. Without the Christian worldview, the unregenerate heart is still back in the garden running from the Lord, burying the truth of God in different “clothes,” systems of belief or disbelief. Because of the number of systems out there, the non-believer may run for a lifetime—and many do. However, by recognizing Van Til’s articulation of the impossibility of the contrary, the Christian is not responsible to know every system of non-belief to confront. First and foremost, he knows his own belief when he gives his apologia. Appeal to Ultimate Authority The most profound emphasis that Van Til’s thought rests upon is that of appealing to an ultimate authority. This is partly where the term “presupposition” comes from, because in Van Til’s thought, the apologist must locate that appeal to some ultimate authority. For example, in philosophy, one who describes himself as a “rationalist” will appeal to human reason or human thought as the ultimate justification for knowing anything. Van Til is not against reason or rationale at this point, but he does not begin with reason to prove the existence of God, or ultimately appeal to it as his final authority. Rather, Van Til presupposes the inspiration of Scripture, and this provides and satisfies the necessary preconditions for intelligibility, for making sense of and justifying anything. The result is a revelational epistemology. Apart from an appeal to the one true and living God, there can be no justifiable rationale, since the Creator—namely Christ—descends into history to make himself known to humanity. It is He that makes reasoning even possible in this created environment. For Van Til, it is therefore irrational to abandon dependence on the Creator, despite the fact that “the natural man knows but suppresses.”[40]Therefore, to claim autonomy or separation from the sovereignty of Christ is to hearken back to the Creator-creature distinction, which cannot be broken. “Man can never in any sense outgrow his creaturehood.”[41] This is why the Van Til elevates and emphasizes the importance of revelation; an emphasis based on two things: (1) Scripture, and (2) special revelation, of which scripture is a part, though it also includes Christ becoming flesh and dwelling among his creatures.[42]This separates Van Til even further from other apologists who share “common ground” with Van Til. The differences, in Van Til’s assessment, between the Arminian and the Romanist are stark. For example, the Romanist says that scripture is necessary, but Van Til’s contention with the Romanist is not regarding the necessity of Scripture, but rather its sufficiency. Because Scripture is sufficient, nothing can be added to it. This also creates a distinction between Natural Theology and Reformed theology. Man cannot come to a saving knowledge of Christ apart from Him because man does not seek after Him. Likewise, the knowledge he has of his Creator is not a saving one, but a damnable one. This is why evangelism is such a prevalent in Van Til’s thought; Romans 1:16 illumes the means by which God is pleased to gather his elect. It is therefore not the lack of reasoning or rationale that “brings one into the Kingdom,” but God Himself, who chooses whom He will save. This view of election may cause one to ask, “Does this weaken the call for apologetics in Van Til’s method?” The answer in Van Til’s thought is a resounding “no.” Rather, a high regard for God’s Word compels us to obey God by preaching the gospel. Secondly, our ignorance regarding the identity of the elect means that we must preach the gospel to all people. Van Til’s own actions—that of street preaching and publicly evangelizing—are a reflection of this. They are a consistent outworking of his method. Book Summary Van Til’s book in many ways is largely inaccessible to those who do not have prior knowledge of his other work, or a working understanding of apologetics—specifically that of presuppositionalism.[43] Much of his vernacular is steeped in the language of continental philosophy, since many of the objections to his method came from this realm. Van Til’s work in The Defense of the Faithreiterates much of what he had already articulated elsewhere, but also with defenses and replies to many of his critics. Most notable, however, is the prime thrust of Van Til’s apologetic to be consistent with Reformed theology—not adding anything new to theology, but also not setting theology aside when engaging in apologetics.[44] This book comprises the broadest defense of his apologetic method in any single work, one that had not changed years after its publication when he wrote Christian Apologetics.[45] It is notable that many of the various criticisms against Van Til disagree with one another. In fact, in many ways they seem to suggest that they did not fully know or understand the implications of Van Til’s newly articulated method.[46] Lastly, this particular work is interesting in that it gives replies to his critics by providing a structure and summary rationale for this line of thought. It is an insertion that allows the reader to step into Van Til’s thinking easier than he could without it.[47] Book Format The primary focus of the book is a reply and re-articulation of what Van Til had already espoused. Because of that, and because the book is a defense of his method, Van Til offers a unique way of understanding his method, which we can see in the way he formats the text. The text is divided into two main parts: (1) the structure of Van Til’s thought, and (2) a reply to objections. The first division begins with that which is fundamental to all of Van Til’s method: theology. His Reformed theology places an emphasis on (a) the doctrine of God, (b) the doctrine of man, (c) the doctrine of Christ, (d) the doctrine of salvation, e) the doctrine of church, and (f) the doctrine of last things. These divisions are systematic in the way they correspond to other Reformed thinkers. For example, Van Til’s starting point is the same as Calvin’s in speaking about knowledge of God, and knowledge of the self. It also cannot be emphasized enough that Van Til begins by outlining key doctrines of theology that were fundamental to understanding and doing apologetics. By no means is he trying to suggest his sections on Doctrine, Salvation, etc, are exhaustive—simply that they are fundamental, foundational starting points to doing apologetics. The Second division of this book deals primarily with objections to: (1) theology, (2) metaphysics, (3) epistemology, (4) apologetics and (5) common grace.[48] This work is thus considerably longer than many of his others because Van Til’s emphasis is not only to bring clarity to apologetics, but to offer an “apologetic” for his apologetic. With the considerations and objections in mind, Van Til’s aim is not to create a “how to” for the Christian to practice apologetics (such as his smaller work Christian Apologetics), but rather to give a defense of his own apologia. Doctrine Van Til’s doctrine was not distinctively his own. As Scott Oliphint describes it, “what Van Til was advocating was both old and new. It was old in that he was applying the basic tenets of Reformed dogmatics to apologetics […] it was new in that apologetics, prior to Van Til, had taken less notice of theology as the springboard for its tasks and more the notice of philosophy.”[49] In fact, Van Til did not want to offer anything new in terms of doctrine; he only wanted make apologetics consistent with doctrine. This being said, Van Til was Reformed, and in his own words at the start of his book he writes, “I therefore presuppose the Reformed system of doctrine.”[50] It is fairly easy to re-summarize what Van Til believed doctrinally, because this was his starting point. This begins with an ultimate pre-commitment to Scripture, a view in a Reformed interpretation that understands humanity as fully dead in their sins as creatures, and fully dependent on the Creator who chooses who to regenerate the sinner. This comes by the means of God’s free choice and will upon those dead in sin, by the power of the Holy Spirit through granting of repentance in order to redeem man’s fallen reason. Or as Paul writes in his epistle to the Romans, to be predestined, called, justified, and one day glorified.[51] Criticism & Impact Van Til has been immensely influential in Christian apologetics. Probably the most critical theologian of his thought came from within the Reformed camp: R.C. Sproul.[52] Although there are notable detractors from outside and inside of the Reformed tradition, the notable people who have followed in Van Til’s presuppositional, Reformed milieu is worth mentioning: Rousas Rushdoony, John Frame, Greg Bahnsen, Scott Oliphant, William Edgar, Francis Schaeffer, James R. White, Gary DeMar and many others.[53] Even more interesting is that Van Til’s apologetic methodology has not been limited to just the academic world. This is something quite profound about the prepositional method of Van Til’s thought; it is a method that the layman can employ with a “nuclear strength.” For example, notable street preacher Tony Miano describes himself as a presuppositionalist, and employs such an apologetic in his field of evangelism. Likewise, pastor and host of Apologia Radio, Jeff Durbin, is one of the most outspoken street-level evangelist-apologists to religious cults. Others like Sye Ten Bruggencate have been featured in training videos for the church in how to employ presuppositional apologetics. Scott Oliphant, too, was recently interviewed on the Unbelievable Program in London about presuppositional apologetics and its differences with Natural Theology. Van Til’s apologetic has become accessible to more and more spheres within the church and has gained traction in recent years. Classical and evidential apologetics dominate much of the broader scene in apologetics, but it no longer has a monopoly on apologetic method. The impact that Van Til’s thought had appears to have continued for many years after his death and is carried on by those who were trained in his approach. Notes: [1] Van Til had already published several other books, articles and syllabi on his methodology. But this was the first work in which he wrote significantly longer responses to the objections to his methodology. The method he was defending, therefore, was not confined to one work, but his entire work up to that point. [2] There are, as John Frame points out, specific examples that go against this generalization. For example, Augustine and Anselm make reference to ideas that have strong resonances with some of Van Til’s presuppositional thought. Nevertheless, the generalization is still agreed upon by Frame and others. See John Frame, Christian Apologetics. [3] This particular separation was something on which Van Til disagreed with Warfield. See Bahnsen, Van Tillian Apologetics Part II. [4] The issue here, as will be fleshed out below, is not simply whether there is a reference to Scripture but how Scripture was used in direct respective to final and ultimate authority. Specifically, this intersects with epistemology and justifying one’s ability to know anything. [5] Greg Bahnsen, "Van Tillian Apologetics Part II," Westminster Theological Seminary, April 12, 2012, [6] John M. Frame and Cornelius Van Til, Cornelius Van Til: An Analysis of His Thought (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Pub., 1995), 45. [7] Nathan D. Shannon, "Christianity and Evidentialism: Van Til and Lock on Facts and Evidence," Westminster Theological Journal 74 (2012): 336. [8] William White, Van Til, Defender of the Faith: An Authorized Biography(Nashville: T. Nelson Publishers, 1979), 24. [9] Ibid. pg 37. [10] Ibid. pg 67. [11] Modernism is itself a difficult term to define, since there are great disagreements as to its meaning, and when the “modern era” actually began. Its use here is probably best typified with the undertones of one foot in a Darwinian worldview and the other in liberalism, likened to that of German Higher Criticism. [12] Understanding Machen’s own story in founding Westminster would be particularly beneficial to those wanting to understanding this context. Specifically, the grounds on which he was dismissed from Princeton without trial as well as the series of lectures and radio addresses on liberalism that became the basis for his book, Christianity and Liberalism. [13] Ibid. pg 82. [14] A syllabus of the day is not the same as a syllabus that is typically associated with course work today. This was not a list of a professor’s expectations and course requirements, but essentially books that were written specifically for a class. An example of these readings can be found in Van Ti’s Apologetic: Readings and Analysis by Bahnsen. This is perhaps one reason why Van Til is thought to be inaccessible, because much of the material he produced assumed a higher caliber of student to understand it; and yet, these readings are still available, often without explanation as to what seems at first to be an unusual format. [15] Ibid. pg 190. [16] John M. Frame, "Christian Apologetics - Dr. John Frame," ITunes U: Reformed Theological Seminary, November 9, 2011 [17] Greg Bahnsen, Francis Schaffer, Gordon Clark and others use different definitions for this term, yet identified themselves as such. Thus, this has prompted Scott Oliphant to label Van Til’s specific method Covenantal Apologetics, in order to differentiate it from the other strains of presuppositionalism. For a fuller discussion, see K. Scott Oliphint, Covenantal Apologetics: Principles and Practice in Defense of Our Faith (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013). [18] The term seems to have been first described of Van Til by J. Oliver Buswell when he criticized Van Til’s methodology. Buswell referred to Van Til as the “fountainhead of presuppositions.” His use was, in some sense, meant to be a critique. [19] John M. Frame and Cornelius Van Til. Pg 136. [20] Ibid. [21] K. Scott Oliphint, "Covenantal Apologetics," Theology, Philosophy & Science, September 9, 2013, [22] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith, Fourth ed. (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Pub., 2008 (1955), 95. [23] Cornelius Van Til and William Edgar, An Introduction to Systematic Theology: Prolegomena and the Doctrines of Revelation, Scripture, and God (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Pub., 2007), 29. [24] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith. Pg 94. [25] Ibid. Pg 92. In this section, Van Til is dealing specifically with what he describes as Romanism. [26] James Anderson, "If Knowledge Then God: The Epistemological Arguments of Alvin Plantinga and Cornelius Van Til," Calvin Theological Journal 40 (2005): 50. [27] John M. Frame, "Christian Apologetics - Dr. John Frame," ITunes U: Reformed Theological Seminary [28] Romans 1 [29] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith. Pg. 96. [30] Henry Krabbendum, "Cornelius Van Til: The Methodological Object of a Biblical Apologetics," Westminster Theological Journal 57 (1995): 126. [31] Van Til equates Natural theology with Roman Catholicism because of their shared starting point. [32] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith. Pg. 101. [33] William D. Dennison, "Van Til and Common Grace," Mid-America Journal of Theology 9, no. 2 (1993): 229. [34] Ibid. 229. [35] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith. Pg. 116. [36] Scot Oliphant adds a great deal of clarity to this line of thought in Covenantal Apologetics. [37] R. John. Rushdoony, Van Til (Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1960), 18. [38] As the following heading indicates, this concept was fleshed out to be more accessible and cogent by Greg L. Bahnsen in his succeeding work. It was Bahnsen who re-appropriated the “opposite” to be “contrary.” See Greg L. Bahnsen and Joel McDurmon, Presuppositional Apologetics: Stated and Defended (Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, 2008), 124. [39] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith. Pg. 122. [40] Ibid. pg 124. [41] Ibid. pg 35. [42] John 1:1, 14 [43] This is not my assessment alone, but that of Bahnsen, Frame and Oliphint. [44] As Scott Oliphant notes in analyzing his arguments that, although there is development of thought, it is consistent with his prior work in The Defense of the Faith. Scott Oliphint, "The Consistency of Van Til's Methodology," Westminster Theological Journal 52 (1990): 42.. [45] One can note almost right away the remarkable consistency between the sections The Defense of the Faith and Christian Apologetics under Authority and Reason. Pg 161. See pg. 144 of The Defense of the Faith to compare. [46] There are several reasons to suggest this. One comes from Van Til himself, but also those that followed in his tradition who admit that Van Til was not always clear in what he was arguing, even though his ideas were most definitely profound. One particular criticism mentioned in his work comes by Van Halsema, who states, “Cur spargit voces in vulgum ambiguas?” Translated meaning: “Why does he scatter ambiguous words on the people?” Oliphint notes that this is used to criticize Van Til as one who “clouds an issue to win a debate.” [47] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith. Pages 203-383. [48] It should be noted that the diversity of objections came from a very wide array of thinkers in theology and in philosophy. The impact of Van Til was not limited to one field, but crossed into several. [49] Cornelius Van Til and K. Scott Oliphint, The Defense of the Faith. Pg 27. [50] Ibid. [51] This order of salvation is directly from Romans 8:28-30. This also known as the Golden Chain of Redemption. [52] See R. C. Sproul, John H. Gerstner, and Arthur Lindsley, Classical Apologetics: A Rational Defense of the Christian Faith and a Critique of Presuppositional Apologetics (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1984), for a description and criticism of Van Til’s approach. [53] Most definitely differences in the presuppositional approach exist among those that succeeded Van Til, but generally speaking, these individuals seem to closely align with his thought.

1 Comment

|